Honeybees will soon be out seeking nectar and pollen.

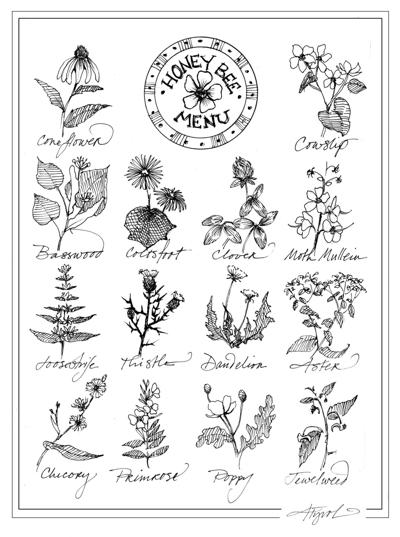

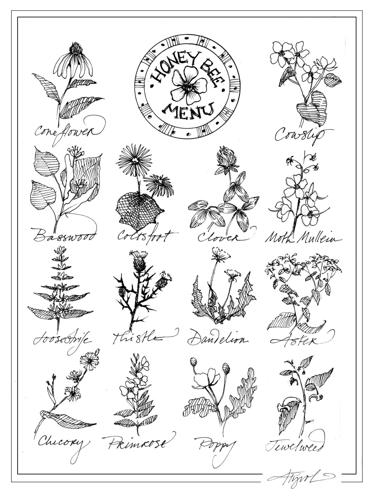

From early-blooming red maple trees. Then sugar maples, apple trees, dandelions. From blueberries, raspberries, and blackberries. From clover, staghorn sumac and basswood trees. From milkweed, coneflowers, thyme, and sage. From asters and goldenrod; jewelweed and Japanese knotweed. For a bee, the warmer seasons are a Mardi Gras parade of nectars.

In a good year a hive can produce 60 pounds or more of surplus honey. But mileage may vary — much about production, and flavor, depends on weather and location.

We call the multi-floral honey from our 30 or so hives “wildflower honey.” So-called varietal, or monofloral, honeys come (mostly) from a single flower source. There are some 300 types of honey produced in the United States, according to the National Honey Board. Most varietal honeys are produced by commercial beekeepers who move their hives from place to place to pollinate crops, or simply to take advantage of a “honey flow” from a particular plant.

Florida is famous for orange blossom honey, Maine for blueberry honey. There’s light clover honey, and dark, strong buckwheat honey.

Although monofloral honey may have less variation, each batch is still unique, because plants change across the landscape, and weather – temperature, rainfall, timing of rains – is always different.

Honey is 95 percent carbohydrates, mostly sugars, and mostly fructose and glucose. “The Hive and the Honey Bee” notes that recent research has “revealed honey to be a highly complex mix of sugars” major and minor. “Many of those sugars are not found in nature, but are formed during ripening and storage by bee enzymes and the acids of honey.” Isomaltose, anyone? What about a little laminaribiose?

Honey flavors also vary because of the volatiles that flowers use as attractants, said Kim Flottum, editor of Bee Culture magazine and co-author of “The Honey Connoisseur.” This is why honey often tastes and smells like the plants the nectar came from. Flottum emphasized that the influences on honey flavor are complex, and extend well beyond sugars and volatiles, including the water the nectar plant “drinks,” the nutrients it absorbs, the acidity of the soil that it grows in, and the chemicals it produces to protect itself. “The final ingredients are almost infinite,” he said.

Charles Mraz of Champlain Valley Apiaries is a third-generation bee keeper. His company produces tens of thousands of pounds a year from 700 or so hives. He calls his honey clover honey, but a lot of other plants are in there as well.

Working his bees during the summer Mraz can often tell, by taste or smell, what plants they’ve been visiting. “I can certainly distinguish a clover flow, a locust flow and a goldenrod flow,” he said. “The bigger ones are quite distinguishable.”

Mraz says Vermont’s multifloral honeys are truly “magical.”

“I think the honey we get here in the Champlain Valley of Vermont has a really remarkable flavor and a complex range of flavors,” he said. “I think a lot of what makes our Vermont honeys so complex is the variety of our honey sources.”

Joe Rankin lives, writes and keeps bees in Maine. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of N.H. Charitable Foundation.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexual language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be proactive. Use the "Report" link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.