Bullwinkle is in trouble, and if you want to know why, look to his forest cousin Bambi. This is no cartoon, though: It’s a real-life story with an uncertain ending and a lot of concerned viewers watching closely.

The lives of the moose and the deer have become twinned today in a fascinating interplay of habit and habitat, evolution, human intervention and climate change. For hunters and an expert cadre of wildlife biologists, each turn of the year offers new clues and new uncertainties for the future of Alces Canadienses, the fabled Eastern moose.

Vermont’s two largest mammals are linked by genetic family, mythic reputation and size, as well as their important role in Native American and Vermont culture. And, it turns out, they are linked as well by the pests that plague them, with serious consequences for the moose.

The mighty buck, with its noble head and antlers, remains the top mammal in the Vermont pantheon. But in terms of massive size, ungainly looks and ponderous racks that spread more than 50 inches and can weigh 70 pounds — amazingly grown each year — the deer is no match for the moose.

That largely explains why the moose was hunted and extirpated on our landscape by the late 1800s, not to reappear until the 1970s, when moose wandered south from Maine after that state decided to ban moose hunting in 1950 to preserve the animal.

The Algonquin gave the moose its name, which translates to “twig eater,” reflecting the tree browse, bark and aquatic plants that compose its diet. For Native Americans and colonialists, the moose was a sustaining savior, providing tasty meat to fend off starvation.

Today’s hunters value it no less, whether they come armed with rifles, bows and arrows or, increasingly, a pair of binoculars and a hankering just to watch the animal in the wild.

For 23 years, no one has watched moose more closely — from microscopic and skin level to antlers and population — than Cedric Alexander, the wildlife biologist who oversees moose for the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department. In that time, he has seen a dizzying ascent and then troubling decline in moose numbers and health.

Both as a good scientist and because he cites past forecasts of the moose’s fate that were wildly off base, he is cautious with predictions. But, like many, he wonders if the writing is on the wall — or in the forest.

“There are people who are concerned that the climate is changing so that the moose is not going to find suitable habitat or living environment here,” he says. “If it keeps getting warmer and some of the parasite loads are heavier because of that, who knows.”

A trio of woes that would shock even the biblical character Job are at play. Two are intertwined with lives of the deer: the awful winter tick, and the equally awful brainworm. Neither harms deer, but they afflict the moose in ways not only pestilential, but fatal.

The third factor is our warming climate, which is making life harder for a circumpolar species that evolved to thrive in cold, snowy regions and does not handle heat well.

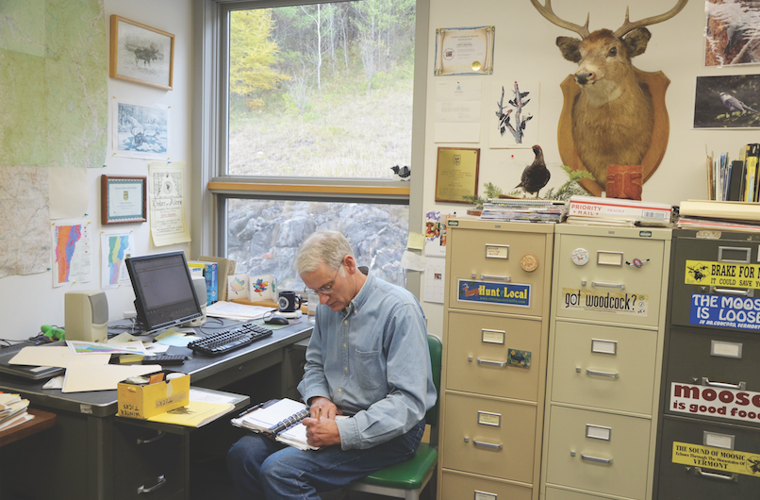

If you want a walking Wikipedia of the moose, not to mention the threats that assail it, then Alexander is your man.

In his jam-packed office in St. Johnsbury, he has vials of moose ovaries and ticks in all life stages, boxes of jawbones and antlers, teeth and other items that he brings on show-and-tells. He has every chart imaginable, from a tally of the just-finished hunt this year — he’s counted 147 so far, about as predicted — to how many moose have been killed by hunters since seasons began in 1999: about 6,150.

Here’s another figure: More than 3,000 have died in car accidents, along with 18 drivers.

“The first motor vehicle mortality was in 1981,” says Alexander, standing over binders of color charts. He’s a rangy, lean fellow, erudite on all things moose, easily able to go as deep into the weeds as you like on moose.

These days increasingly it’s dermacentor albipictus, the winter tick, that Alexander is watching. Thanks to a complex permit system that divides the state into management zones, he says, the state has done a good job keeping moose populations in balance with their food and habitat, while providing hunters the chance of a lifetime with lottery permits since 1993.

But human management is being undone by other factors.

“When European colonists came and changed the landscape, we ended up making conditions more favorable for deer to extend their range northward,” he explains. Deer are nimble and have learned how to groom themselves to pick off winter ticks. But moose are not, and with both now cohabiting the same ranges, the ticks have become a scourge for moose.

“Moose didn’t have winter ticks in their environment, they didn’t have eons of evolution in their environment to adapt to it,” he explains.

The winter tick is appalling. After larvae develop on the forest floor, thousands of the tiny orange insects ascend vegetation in fall and, when a moose brushes by, the entire clump will grab on in what Alexander calls a “tick bomb.”

Females grow as big as an olive pit and moose can find themselves hosting 50,000 of the blood-sucking pests, which embed and feed throughout the winter and then drop off in spring. Moose, and especially calves, can literally die of anemia or pure aggravation.

“That’s one of the issues. They spend two and a half hours a day grooming instead of feeding and resting, where normally they would spend 30 seconds,” he says.

Moose will rub themselves down to raw skin trying to dislodge the ticks, stripping away insulating hairs so they die of hypothermia.

The engorged ticks drop off in April, which is where Vermont’s warming climate comes into play. In the past, Alexander says, in the North Country snow lasted well into April, and ticks dropping off into snow likely would not survive. But in seven of the past 10 winters, the snow was gone in April, allowing the ticks to land in leaf litter and thrive.

Now consider the brainworm. Alexander says tests of deer feces, where brainworm eggs are expelled, show 80 to 90 percent contain the worm. Deer appear unaffected by brainworm, a hair-thin 3-inch parasite. But in moose the worm causes all kinds of inflammation and brain damage that leads to the nickname “circling disease,” because partially paralyzed moose tend to go in circles and eventually die.

“The moose is a dead-end host,” says Alexander.

Whether all these factors spell the end for the moose in Vermont is the big question today. “They are pretty resilient,” he says, but Alexander’s charts reveal moose health has declined by many measures, from birth rates to body weights.

If the moose vanished again from Vermont’s landscape, he says it would be a dramatic step backward.

“If would be a huge loss if it came to the point where that was lost again, because you’re really re-creating what the Abenakis and the early colonists had … how they lived off the land,” he says.

(1) comment

My scouting & hunting in zone E2 (NEK) has shown a much higher moose density than F&W estimates. In a 5 sq. Mile area I had a dozen different Mature bulls on 9 scouting cameras, and at least as many juvenile bulls (harder to differentiate, as juvi racks are similar). I did not try to count cows/calves as they look alike. He mature bull I harvested had very few ticks on him, so I am hoping the tick issue was a cyclic surge that has peaked and regressed. I do feel the moose have moved further from roads and areas they have felt high hunting pressure in the past.

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexual language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be proactive. Use the "Report" link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.