This summer is forecast to be a busy one for ticks, particularly for cases of Lyme disease. And you can probably blame the humble acorn.

In 2015, the oak trees in New York’s Hudson Valley were heavily laden with the fruit. Anyone who’s lived near oak trees — particularly anyone with a metal-roofed house — knows there are some years when the number of nuts is higher than others. And 2015 was one of those years where acorns were falling from trees like rain from the sky.

It was a bumper crop that had some scientists concerned. Not because there’s something inherently bad about a lot of acorns, but because of what they foretold.

Rick Ostfeld is an ecologist with the Cary Institute, a leading environmental research organization, located in the heart of the Hudson Valley. In a 2015 interview with Northeast Public Radio, Ostfeld predicted that this year would be one of peak prevalence for ticks.

Why? Because a heavy acorn crop in one year — referred to as a “mast year” — leads to a dramatic spike in the population of white mice the following year. All those wee rodents running around that summer can only mean one thing for the following year: lots and lots of ticks.

“The ticks that are emerging as larvae in August — just as the mice and chipmunks are reaching their population peaks — they have tons of excellent hosts to feed from,” Ostfeld said in 2015. “They survive well and they get infected with tick-borne pathogens. And that means that two years following a good acorn crop we see high abundance of infected ticks, which represents a risk of human exposure to tick-borne disease.”

Which means it’s time for a summer-long picnic. And you’re the main course.

“Nasty little filthy things”

Bradley Tompkins, an epidemiologist with the Vermont Department of Health, doesn’t mince his words when it comes to ticks.

“They’re just nasty little filthy things that serve no evolutionary purpose whatsoever,” Tompkins said last week.

Maybe so, but those eight-legged pestilence spreaders — and it’s not just Lyme disease anymore — have evolved to become a remarkable carrier of disease, largely by getting really good at being carried along.

The deer tick, or blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis, is tiny enough that you have to sometimes search hard to find them on your body, although they’re prevalent enough this year that outdoorsy types — from hikers to golfers with a tendency to hit their balls into the woods — can nearly assume they’ll come home with a few extra passengers.

Another reason you might not notice you’ve got ticks on you: you probably won’t feel it when the deer tick shoves its beak-like mouth into your skin because it releases a sort of antihistamine as it feeds, according to Tompkins.

Ticks aren’t particularly mobile, although you can sometimes feel them crawling up and down your skin, before they stick their mouthparts into you. Tom Rogers, a Stowe resident who works with the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department, said he was down near Springfield last week with a crew, and each of them ended up with about 20 ticks on them.

“On our way back to Stowe, holy cow, we were just peeling them off,” Rogers said. “Every five minutes someone would roll down the window and toss another tick out.”

When he got home, he stripped to his underwear, and had his wife give him a once-over. Sure enough, there was one square in the middle of his back, looking like it was about to feed.

Worse than Lyme

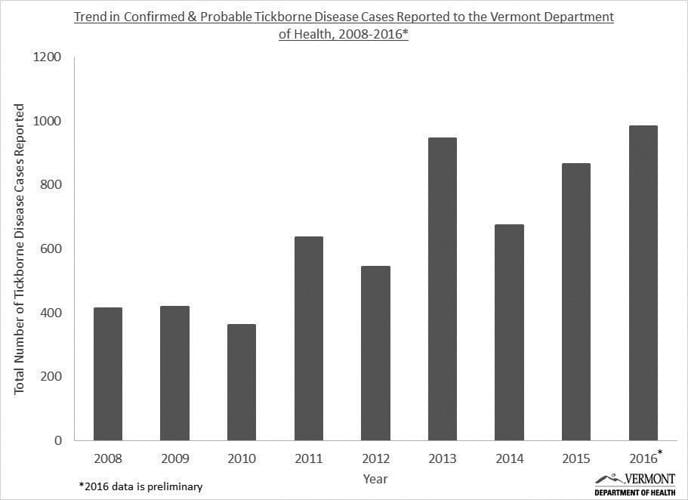

According to Tompkins, most people think Lyme disease when they think tick bites, and for good reason. The disease affects about 300,000 Americans each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The disease carries with it symptoms similar to the flu — aches and pains, fatigue and fever. And it can last a long time, as long as half a year for some sufferers, even with treatment. Deer ticks are the primary carrier of Lyme disease, the smaller the tick the more likely it’s a carrier.

A tell-tale bullseye rash around the bite accompanies most cases of Lyme disease. But, according to Tompkins, the department of health is noticing an uptick in another, more harmful disease.

Anaplasmosis is another bacterium carried by the same type of tick that carries Lyme disease, although it appears to affect older people more often than younger. Tompkins said the disease frustrates medical professionals because it has all the same symptoms as Lyme, but without the tell-tale rash.

And it’s worse.

“Lyme is no joke, but as an acute disease, only about 3 percent get hospitalized, whereas anaplasmosis is about 36 percent hospitalization,” Tompkins said. “I hope it’ll never become as common as Lyme disease.”

Tompkins’ advice for dealing with anaplasmosis and Lyme disease is simple.

“Look, if you’re feeling horrible in the late spring and early summer, and flu season is over, go to the doctor,” he said.

Better check yourself

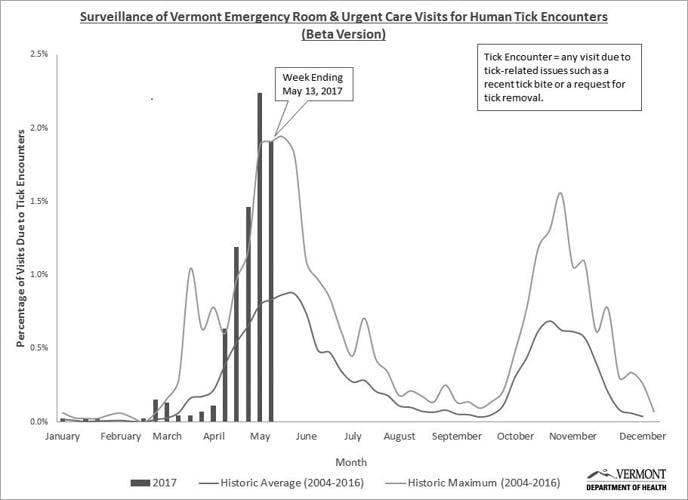

Col. Jason Batchelder, the head of the fish and wildlife department’s enforcement division, said the hotspots for tick activity in Vermont remain along the Connecticut River valley, as has been the case for about a decade. However, the Champlain Valley, with its early spring dry and warm spells, is also rife with the buggers.

They’ve also begun popping up in Stowe, Waterbury and Morrisville. Batchelder lives in Elmore, and he hasn’t seen any on his property, but he said neighbors who live just 500 feet lower in elevation on the Elmore Mountain Road have spotted them.

The department doesn’t keep tabs on tick activity, although anecdotal evidence abounds. And there isn’t a plan to eradicate the population.

“It’s about checking yourself all over, without getting involved in spraying the whole world, which is something we’re not going to do,” Batchelder said.

The department recommends four steps to staying disease-free:

• Repel the ticks by using bug repellent and treating clothes and gear with permethrin. And wear long-sleeved shirts and pants, and tuck your pants into your socks.

• Inspect yourself, your kids and your pets. Furry dogs are like magnets for the arachnids.

• Remove the ticks as soon as possible — it’s been said that it takes 24 to 36 hours with a tick embedded in you to contract a disease. It could be as easy as taking a shower within two hours of coming in from an outdoors adventure.

• Keep an eye on your health if you suspect you were bitten and call your doctor if you experience fever, muscle aches, fatigue, or joint pain.

Rogers said some people are wary of the wrong beasts out in the wild. Size doesn’t matter, unless that size is super small.

“We’ve got rattlesnakes, we’ve got black bears, and all these things we traditionally should be afraid of, but neither of those things will typically hurt you. They’re not bearing down on you with teeth and claws,” Rogers said.

Just be prepared. And keep an eye on those acorns.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexual language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be proactive. Use the "Report" link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.